In the pandemic of 1918, between 50 and 100 million people are thought to have died, representing as much as 5% of the world’s population. Half a billion people were infected.

Especially remarkable was the 1918 flu’s predilection for taking the lives of otherwise healthy young adults, as opposed to children and the elderly, who usually suffer most. Some have called it the greatest pandemic in history.

The 1918 flu pandemic has been a regular subject of speculation over the last century. Historians and scientists have advanced numerous hypotheses regarding its origin, spread and consequences. As a result, many harbor misconceptions about it.

By correcting these 6 misconceptions, everyone can better understand what actually happened and help mitigate COVID-19’s toll.

1. The pandemic originated in Spain

No one believes the so-called “Spanish flu” originated in Spain.

The pandemic likely acquired this nickname because of World War I, which was in full swing at the time. The major countries involved in the war were keen to avoid encouraging their enemies, so reports of the extent of the flu were suppressed in Germany, Austria, France, the United Kingdom and the U.S. By contrast, neutral Spain had no need to keep the flu under wraps. That created the false impression that Spain was bearing the brunt of the disease.

In fact, the geographic origin of the flu is debated to this day, though hypotheses have suggested East Asia, Europe and even Kansas.

2. The pandemic was the work of a ‘super-virus’

The 1918 flu spread rapidly, killing 25 million people in just the first six months. This led some to fear the end of mankind, and has long fueled the supposition that the strain of influenza was particularly lethal.

However, more recent study suggests that the virus itself, though more lethal than other strains, was not fundamentally different from those that caused epidemics in other years.

Much of the high death rate can be attributed to crowding in military camps and urban environments, as well as poor nutrition and sanitation, which suffered during wartime. It’s now thought that many of the deaths were due to the development of bacterial pneumonias in lungs weakened by influenza.

3. The first wave of the pandemic was most lethal

Actually, the initial wave of deaths from the pandemic in the first half of 1918 was relatively low.

It was in the second wave, from October through December of that year, that the highest death rates were observed. A third wave in spring of 1919 was more lethal than the first but less so than the second.

Scientists now believe that the marked increase in deaths in the second wave was caused by conditions that favored the spread of a deadlier strain. People with mild cases stayed home, but those with severe cases were often crowded together in hospitals and camps, increasing transmission of a more lethal form of the virus.

4. The virus killed most people who were infected with it

In fact, the vast majority of the people who contracted the 1918 flu survived. National death rates among the infected generally did not exceed 20%.

However, death rates varied among different groups. In the U.S., deaths were particularly high among Native American populations, perhaps due to lower rates of exposure to past strains of influenza. In some cases, entire Native communities were wiped out.

Of course, even a 20% death rate vastly exceeds a typical flu, which kills less than 1% of those infected.

5. Therapies of the day had little impact on the disease

No specific anti-viral therapies were available during the 1918 flu. That’s still largely true today, where most medical care for the flu aims to support patients, rather than cure them.

One hypothesis suggests that many flu deaths could actually be attributed to aspirin poisoning. Medical authorities at the time recommended large doses of aspirin of up to 30 grams per day. Today, about four grams would be considered the maximum safe daily dose. Large doses of aspirin can lead to many of the pandemic’s symptoms, including bleeding.

However, death rates seem to have been equally high in some places in the world where aspirin was not so readily available, so the debate continues.

6. The pandemic dominated the day’s news

Public health officials, law enforcement officers and politicians had reasons to underplay the severity of the 1918 flu, which resulted in less coverage in the press. In addition to the fear that full disclosure might embolden enemies during wartime, they wanted to preserve public order and avoid panic.

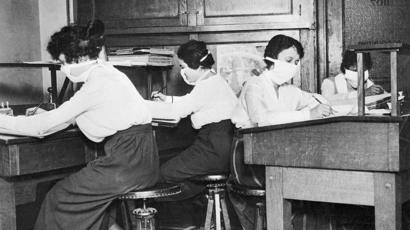

However, officials did respond. At the height of the pandemic, quarantines were instituted in many cities. Some were forced to restrict essential services, including police and fire.

Source: http://www.snopes.com

Hmmmm.. So you think with the help of technology in our era they can come up with the vaccine pretty soon?

LikeLike

I believe coming up with vaccine to cure the disease is it going to take a lot of processes.Just recently it was on a foreign news that people had sacrificed themselves for the newly created vaccine to be tested on them and I further read that even if its successful its going to take 18 months for everything to be finalize and then,treatment of patients begins.

LikeLike